These siblings took DNA tests and got different results. Why determining ancestry is rarely accurate.

The Philadelphia Inquirer

Determining your precise ethnicity under any circumstances is iffy. Ancestry.com seems to try as hard as anyone to get it right.

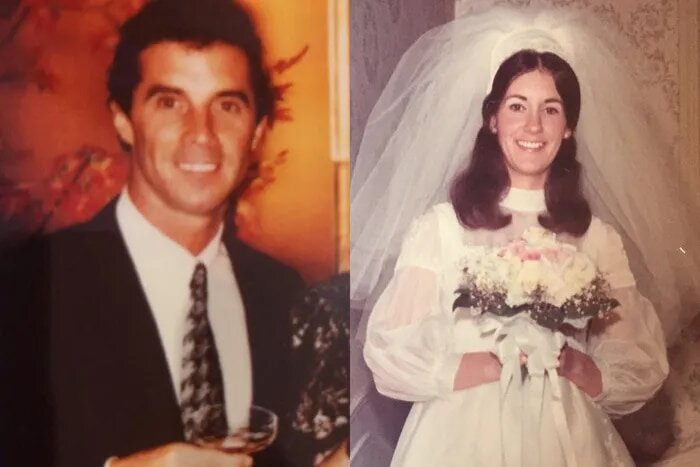

Bob Carden, left, and his sister Barbara, right.

by Bob Carden, For The Inquirer

Published Oct 18, 2017

My wife bought the Ancestry.com DNA test for my birthday. Great gift, cheap, easy and fun. Everyone is doing it. Six weeks after sending in the spit, I got the results. Nicely presented — colorful graphs and charts — but they seemed a bit off and more vague than I had expected.

For instance, my grandfather was an immigrant from Greece. He came through Ellis Island in 1911. I figured that made me at least 25 percent Greek. Yet, Ancestry showed a range of 9 to 30 percent Italy/Greece, with a likelihood of 18 percent. Vague in itself — not to the mention the fact that mixing Italians with Greeks would have driven my grandfather to the nearest bottle of Metaxa.

Bob Carden’s paternal grandfather, of Greek descent, and paternal grandmother, of Irish descent.

Nevertheless, I thought little more of it until I mentioned the test to my sister Barbara. Unbeknownst to me, she'd had the test done, as well, and was awaiting the results. They came a week later. And those results were more than just a bit off.

Our Italy/Greek numbers were about the same. But her results showed 37 percent British Isles, whereas I was 53 percent. She also showed 10 percent Scandinavian and 7 percent East Europe — neither of which even appeared in my results. And we're about as Scandinavian-looking as Jennifer Lopez.

Let's chase the elephant out of the room. The odds that my happily married and saintly mother might have had a dalliance, with, say, a Norwegian sailor back in the 1950s are nil.

Barbara Rettaliata on her wedding day in 1972 pictured with her parents Jim and Bette Carden.

So, same parents, different DNA test results. What gives?

"It's very difficult to accurately find your ancestry under any circumstances," said Jonathan Marks, an anthropology professor at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. "There has been genetic mixing for thousands of years. These tests are fun but rarely accurate — 10 percent Scandinavian could be no Scandinavian because the test could very easily be 10 or 15 percent off."

The imprecisions are not limited to Ancestry. My sister's son took a DNA test from 23andMe, another popular DNA testing company. His father is Italian and Irish, named Rettaliata. The test showed no Greek and just 1 percent Italian.

"The methodology they use in determining the DNA markers is solid," said Deborah Bolnick, an anthropology professor at the University of Texas. "The challenges come with interpreting those DNA sequences to say something accurate about your ancestry."

Those challenges sure aren't conveyed in the ubiquitous TV ads. Folksy testimonials from happy customers beam with wonder. "I found out I was 16 percent Italian," says one consumer. Well, maybe you are and maybe not. Experts say assigning a specific percentage is problematic.

"You are dealing with probabilities here, not certainties," said Sarah Tishkoff, professor of genetics at the University of Pennsylvania.

Our genes identify many characteristics about us — for instance, there is a gene that programs eye color. Genes contain DNA, the chemical basis of heredity. A genetic test is never going to be 100 percent accurate in determining ancestries tied to specific ethnic groups. Ethnicity is not a trait derived from a single gene or a combination of genes. If only it were that simple.

Determining your precise ethnicity under any circumstances is murky. Ancestry seems to try as hard as anyone to get it right.

Barbara Rettaliata in her 20s in an undated family photo.

About my sister and me having different results, Ancestry explained that it is not all that uncommon for siblings with the same parents to have different ethnic traits.

"Each parent gives 50 percent of their DNA to you, but the subset of DNA you get could be different from your sibling," says Eurie Hong, senior director of genomics, research and development at Ancestry.

Bolnick agrees that siblings could potentially inherit some different DNA sequences from a parent. But she is a bit skeptical that this could lead to significantly different assessments of the siblings' ancestry.

Still, let's assume my sister did receive a different DNA sequence, which accounted for some variance in the results. That just illustrates the fundamental problem with the tests: too many variables.

Most testing companies compare snippets of a person's DNA to that company's database of DNA markers from people living in various regions of the world. That would work flawlessly if our ancestors had stayed in one place, but they moved around. Once ships and roads were invented, it threw everything off kilter, genetically speaking.

Let's say you had a great-great-great-grandfather from Germany named Otto, who was a playful and libidinous sort. He spends a youthful summer in Italy, where he impregnates a local woman, maybe without even knowing it. He returns home, marries a German woman, and has one son, Hans, your great- great-grandfather. Hans eventually moves to the United States, marries an American woman of Irish descent. They have kids, generations pass, more kids. You are born and grow up confident of your German-Irish heritage.

But Otto's kid in Italy has been growing his family too, having kids and more kids. By the time you are born, Otto's DNA footprint in Italy could be as big as it is in Germany. So when you take the DNA test, your DNA also matches all these people from Italy. Voilà! Ancestry determines you are likely 20 percent Italian.

"If you really wanted to know where your ancestors lived, say 500 years ago, you'd have to compare your DNA to a database of the DNA of people who lived 500 years ago," said Bolnick.

And that's the bottom line: Today's inhabitants of an area might have a different genetic makeup from its ancestral inhabitants. Just because your DNA matches someone who currently lives in a particular region, that doesn't necessarily mean your ancestors came from that place.

It's a particularly knotty problem for African Americans. More than 11 million Africans were forcibly shipped to the Americas during the slave trade and there were no lists of passengers or records. DNA testing might be the only way many African Americans can discover their African heritage. But some experts say there has been too much mixing of west African groups to correctly identify a country, much less a tribe.

"I can tell African Americans where they are from without a DNA test — anywhere between Senegal and Angola," said Bert Ely, professor of biological sciences at the University of South Carolina. "These tests are fine at identifying continents but the more specific you get — in trying to identify countries and tribes — the greater the probability of inaccuracies."

But to many African Americans, the tests have real value, even if they can only give an estimate.

"If the test indicates that your DNA matches the Yoruba in Nigeria, that is some real information for some people, something to hold on to," said Charmaine D. Royal, associate professor of African and African American studies at Duke University.

Regardless, questions about accuracy haven't hurt sales. Ancestry has sold nearly 4 million DNA testing kits at $99 a pop. And sales show no sign of slowing down.

"Even if the numbers are often off, they're still fun to talk about at parties," said Marks.

Link to the Philadelphia Inquirer Article: These siblings took DNA tests and got different results. Why determining ancestry is rarely accurate.

A storm in vacationland: HomeAway’s fees anger renters and owners

The Washington Post

A screen image from VRBO.com shows a listing. Owners can pay HomeAway thousands of dollars a year to list on the site; the firm charges renters a “service fee” that run into the hundreds of dollars. (VRBO/VRBO)

By Bob Carden

June 3, 2016

HomeAway.com, the online vacation rental site, has riled customers with a change in practices that some say has made the getaways of their renters more expensive.

At issue is a new “service fee” that HomeAway imposed in February on renters who book through the company’s site. The move has infuriated property owners, some of whom pay HomeAway thousands of dollars each year to list on the site. They say HomeAway, which owns VRBO.com and VacationRentals.com, is using its market power to hit renters with excessive fees.

“I was blindsided by the fees,” says Ivan Arnold, a Los Angeles-based investor who lists five homes on VRBO.com. Arnold is the lead plaintiff is a class-action lawsuit filed against HomeAway in March, claiming fraud and breach of contract. Arnold claims the service fee has “had a devastating effect on inquiries and bookings. We already pay them to list; they shouldn’t go after our renters as well.”

An image from the VRBO.com website shows a listing, with the service fee highlighted. Bypassing the company’s payment system and fees means a cost to the property owner: a less visible listing. (VRBO/VRBO)

The new owner added the booking charge, levied on all renters of HomeAway sites. The fee is 5 to 9 percent of the rental cost and can add hundreds of dollars onto the price of a vacation rental. Some renters have balked.

By April, the backlash over the fees had hit HomeAway headquarters in Austin, Tex. Tom Hale, chief operating officer, left the company after slightly more than a year in the job. He had become the public face of change, and homeowners had focused their anger on him.

“We appreciate his contributions over the years,” a company spokesman said, declining to comment further on his departure.

HomeAway vigorously defends the fees and plans to use most of the money for marketing, says Jordan Hoefar, corporate communications manager for HomeAway. He adds that booking on HomeAway’s system is safe and secure and should give travelers peace of mind.

“Our book-with-confidence guarantee protects travelers against fraud, double bookings,” Hoefar says. “We guarantee the vacation experience.”

Controlling the process

Its critics say HomeAway is trying to limit owner-renter interaction in order to control the entire rental process.

“I have seen a dramatic drop-off in bookings,” says Larry Grossmann, a Missouri investor who owns four condos in Gulf Shores, Ala. “Renters are angry with the fees.”

In recent years, two basic revenue models for short-term rental companies have emerged. HomeAway’s rival, Airbnb, allows the homeowner to list a property for free. In exchange, Airbnb controls the booking process and does not permit the homeowner and prospective renter to communicate outside Airbnb until the payment is made. Airbnb takes a percentage of the rental (between 6 and 12 percent) and distributes the rental proceeds to the homeowner once the tenant checks in.

HomeAway’s model has always been the opposite. Homeowners pay a listing fee, and the service has been free to renters, who contact the owners directly. They then agree to a price and can either make the transaction among themselves or use HomeAway’s online booking service. This approach allowed homeowners and renters to get to know each other before committing to rent.

“We like to talk to the [prospective] tenants before we rent,” says Eric Karla, owner of a cabin at Sonora Pass near Yosemite, Calif. “We can vet them. We like to know who is going to be staying in our places. We cannot do that with Airbnb.”

Many homeowners said the original HomeAway model worked well. Homeowners could find tenants at a fraction of what property managers or Realtors charged, and they controlled the whole rental process. It was similar to a nicely designed classified ad site. You post your house, someone sees it, contacts you, rents the house. Clean, simple, profitable for all.

(Full disclosure: I list a property on VRBO and have always been happy with the results. I’ve yet to see a large drop in bookings, though this is not my rental season. I do not use HomeAway’s online payment system and am not a party to the lawsuit.)

By 2014, HomeAway’s revenue had grown to almost $500 million. Along the way, the company acquired more than 20 competitors around the globe and now lists more than 1.2 million homes worldwide. More than 800,000 of these properties use HomeAway’s booking service, according to the company.

While HomeAway and Airbnb dominate the short-term rental business, HomeAway has traditionally been much stronger in vacation rentals. Airbnb typically has attracted shorter-term urban dwellers. The two companies increasingly are encroaching on each other’s turf, but HomeAway still is considered stronger in the family rental business.

“I get so many more inquiries from VRBO than Airbnb,” says Grossmann, who lists on both sites. “It’s not even close.”

‘I would never have renewed’

HomeAway’s dominant market position and steady cash flow caught the eye of Expedia. It, too, has grown through aggressive acquisitions, gobbling up Orbitz and Travelocity, among other rivals.

HomeAway declined to comment on the pending litigation, but a company spokesman, Adam Annen, said that discussions about the new fee were in the works “months and months before the Expedia acquisition.”

That rankles Arnold. In November 2014, HomeAway chief executive Brian Sharples told shareholders that HomeAway was “going to be free to travelers.” He then pointed out that TripAdvisor and Airbnb have “chosen to charge big fees to travelers. We’re letting everyone know when you come to our platform, you don’t pay a fee.”

“A little more than a year after saying this, they started charging fees,” Arnold says. “I would never have renewed my listing agreement if I had known about these fees.”

Property owners are not required to use HomeAway’s booking system, so they can steer their renters away from the service fee. But owners say there is strong incentive to use the booking system.

A property owner’s listing position is critical to successful renting. The higher your listing position, the more inquiries and bookings you get. High listing is prime beachfront in this business. When an owner declines to use HomeAway’s booking system, their listing drops in position. Owners who use HomeAway’s online booking system pay $349 a year to list — and those who don’t will pay $499 under a new pricing structure that takes effect in July.

“I only use [HomeAway’s] booking system because I need the good placement listing,” Karla says. “If I get repeat renters, I will have them pay me directly so they can avoid the fee.”

It’s easy to see why HomeAway would want to include the service fee. Last year, the company recorded about $14 billion in transactions. Five percent of that is real money and would more than double its annual revenue.

Patty Craver of Bethesda, Md., has used VRBO for a number of family vacations.

“I think it’s unfair for VRBO to charge owners and renters,” she says. “The fee would be a factor in my decision to use them, but if I found the perfect property I would probably still rent it. Fees are everywhere these days.”

Most homeowners — given HomeAway’s market dominance — have little choice but to stay with the company.

“I am investigating other options, but I am not going anywhere,” Grossmann says. HomeAway “is still the number one source of revenue, even with the drop-off.”

Still, others, such as Arnold, have vowed not to do business with HomeAway again. In fact, he has put two homes in Palm Springs up for sale. He believes the new fee structure will destroy the rental business.

“VRBO was such a great site,” he says. “They made money, we — their customers — made money, renters were happy. That’s all over.”

Link to Washington Post Article:A storm in vacationland: HomeAway's fees anger renters and owners

Behavioral economics show that women tend to make better investments than men

The Washington Post

Behavioral Economics show that men tend to take more financial risks and hold losing stocks longer. (Bill Mayer/For The Washington Post).

By Robert Carden

October 11, 2013

It’s happy hour at Hanaro in Bethesda, and I’m with my wife. We’re there about an hour, gobbling plates of half-price tuna rolls and washing them down with $3.50 Blue Moons. Have to hurry, happy hour ends soon. My wife slows down and cautions me to do the same. I don’t listen. Keep ’em coming, right up to 7 o’clock. Then I get the bill: $75. Yikes, how did that happen? I thought this stuff was half price! Call this stupid male tricks — or behavioral economics.

Behavioral economics tries to figure out why people consistently make irrational financial decisions — like paying $75 to jam 15 orders of sushi down your throat in an hour. The bar happy hour embodies two classic ploys that cause irrational choices: scarcity, get it now before it’s gone; and the idea of getting something for nothing, buy two pairs, get the third free. (You needed that third pair of Birkenstocks?)

“If you think something is going away, it can lead to excessive and desperate consumption,” says George Loewenstein, a professor of economics and psychology at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.Legitimate marketers, con artists and stockbrokers make lots of money off our irrational behavior. I didn’t need that last plate of sushi, and I absolutely didn’t need that last drink. My wife told me to slow down, and I didn’t listen — and while she might say that’s not an altogether uncommon occurrence in our relationship, this time I really should have because I overate, overdrank and overspent. And a load of research in behavioral economics suggests that a man’s portfolio and pocketbook would be a lot better off if we listened more to women.

Terry Odean, a University of California professor, has studied stock picking by gender for more than two decades. A seven-year study found single female investors outperformed single men by 2.3 percent, female investment groups outperformed male counterparts by 4.6 percent and women overall outperformed by 1.4 percent. Why? The short answer is overconfidence. Men trade more, and the more you trade, typically the more you lose — not to mention running up transaction costs.“In our research, male investors traded 45 percent more than female investors,” Odean says. “Men are just making a lot more bad decisions than women. More trading leads to lower performance.”

Stock picking with men is too often about one-upmanship and bragging, says LouAnn Lofton, author of “Warren Buffet Invests Like a Girl: And Why You Should, Too.”

“With men, too often investing is all about keeping score. It’s a macho thing,” Lofton says. “They’re looking for hot stock tips to get the quick win and then talk about it.”

Additionally, men hold onto their losers a lot longer than women. They’re sure the stock will come roaring back — even as it sinks. Academics call it confirmation bias; investment advisers call it boneheaded.

“Women are more loss averse than men, more emotionally unattached and are far quicker to unload losers. Whereas men with their bravado, they don’t want to admit they’re wrong,” says Anthony Zalesky, a certified financial planner who advises individual investors and small businesses.

Bad financial decisions often can be traced back to unwarranted optimism, or the “positivity illusion” that things are going to turn out just right. On paper it sounds good — better to be hopeful right? Not so fast. This tendency clouds critical thinking.

“I like confident clients, but not overconfident ones. I like clients who are secure in a long-term strategy. They won’t react to every bit of short-term news. They won’t listen to the guys screaming loudest on TV,” says Jordan Smyth, managing director of Bethesda’s Edgemoor Investment Advisors. “Once you get caught up in the emotions of investing, you’re going to buy high and sell low. There’s probably a lot of testosterone in some of these decisions.”

Aha, the T word.

Have you seen those TV ads about Low T (low testosterone)? They typically feature a swarthy 50-something, maybe in a Mustang convertible. The ads are often couched between the Cialis and Rogaine spots on, say, the Golf Channel. Apparently, popping a couple of these pills boosts testosterone and thus summons your inner Brad Pitt.

So not only will you be able to land Angelina Jolie, but you’ll jet ski, kayak and climb Mount Kilimanjaro. That’s all well and good, but if you want to trade stocks, you’ll have to leave your inner Brad with Angelina. Because too much testosterone can wreck your portfolio.

“Rising levels of testosterone can lead to irrational levels of exuberance,” says John Coates, a neuroscientist at Cambridge and the author of the book, “The Hour Between Dog and Wolf: Risk Trading, Gut Feelings, and the Biology of Boom and Bust.”

Coates is a former Wall Street trader who began studying the brain and biological implications of trading while working at Goldman Sachs. He performed — in his own words “an act of irrational exuberance by walking away from a high-paying managing directorship on Wall Street for the minimum wage of science.”

But the investing public is better off for it. Coates’s book looks at how our physiology affects decision making and affects risks — he studies things like cortisol and testosterone levels in stock traders. He says, in a bubble market, men become more emboldened and take more risks, while doing less homework, so they get creamed in the inevitable crash. It’s called the “winner effect” and contributes to market meltdowns.

Women produce just 10 percent the testosterone of men, so they are less likely to be swept away in risky gambles. Women probably won’t make as much on the way up — but will lose a lot less on the way down.

“When it comes to trading, men are more hormonal than women,” Coates says.

Take that, Paul Tudor Jones. Last summer, Jones, a billionaire hedge fund guy, stirred the gender pot when he said “you’ll never see as many great woman investors or traders as men.” Jones attributed this to child birth and said a woman loses focus when she has a child.

Coates, in his nicest across-the-pond parlance, says Jones is full of it.

“I think he’s mixing up issues, any important event, like having a child or going through a divorce will affect performance in men or women,” he says. “On the contrary, when women return to the work force, they are so eager to work I find them more focused. Anyone can have an opinion, but that doesn’t matter; data matters. And if you look at brokerage records and hedge fund performance over the long term, women managers generally outperform men.”

Con artists love men, particularly well-educated, optimistic, overconfident ones who think they’re too smart to be taken. These guys are the easiest mark for the crook, according to the FINRA Investor Education Foundation. Gerri Walsh, its president, is an expert on investment fraud and behavior.

“Studies show men tend to be overconfident and less likely to seek another opinion,” Walsh says. Women, she adds are “less excited” about investing. All this leads to less of a gambling mentality among women and makes men more vulnerable to a fraud pitch.

Okay, so now what? Men, it seems, are wired to piddle away money on good sushi and bad stocks.

“Ask and check,” Walsh says. “Develop a plan. Stick to it. And ask questions.” She adds that men are more impulsive investors — so having a plan makes it easier to dial back on emotional investing.

Lofton’s remedies are more challenging to certain men, because they involve listening. And not the kind of “yes, dear” head nodding while watching SportsCenter’s top 10 plays.

“If the man is lucky enough to have a wife or girlfriend, bring them into the discussion, share the decision making with them. Women will tamp down some of the crazier risk,” she says. Legendary Fidelity fund manager “Peter Lynch involved his wife and daughters in a lot of decision making, and he did pretty well,” she says.

On the institutional side, Coates has lots of ideas — among them, financial organizations should hire more women and older (Low T) men. He argues this would lead to less overtrading of accounts, more long-term planning and less volatility. And important people are listening. Britain’s Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (which studied the 2008 crash) recommended a number of Coates’s ideas, including gender diversity in banking and stringing out bonuses over longer periods of time.

Odean and lots of academics say investors shouldn’t even bother trading individual stocks. It’s a loser’s game.

“Trading underperforms a buy and hold strategy,” Odean says. “My advice is to find a good, broad-based diversified mutual fund that has low fees. There are lots out there.”

How prudent. And, most investors, men and women alike, would be better off following it. But at what cost? Do we lose a little of ourselves always doing things the proper way? Don’t we need a little juice, risk, excitement?

Maybe, deep down, boys just want to have fun.

When I’m not pigging out at happy hour, I like to bet horses. But I found I am no better at handling trifectas than I am at resisting bargain sushi and Belgian ales. I’ve lost a lot more than I’ve won. Yet, I still go and handicap because I just know I am going to beat the pros and my big payday is just around the bend. It’s dumb, emotional, positively delusional — I guess I’ll never learn.

Link to Washington Post Article: Behavioral Economics show that women tend to make better investments than men.

Investment fraud isn’t relegated to Wall Street: Beware the Ponzi schemer next door

The Washington Post

By Bob Carden

May 7, 2011

John McKenney’s a smart guy. A lawyer and tax expert, McKenney left Washington a few years ago and moved to Sarasota, Fla. He got a tan, took up yoga, started dating a well-heeled local woman. She brought McKenney into her well-heeled crowd.

Soon, all the heels in the group were clicking about a new, can’t-miss foreign currency deal, paying 5 percent a month, 60 percent a year. The trader doing the deal, Beau Diamond, was young but well known around town. His father, Harvey, was a local health and fitness celebrity.

Diamond said he possessed a secret, proprietary method for trading currency futures. Everyone jumped in, including McKenney. He invested $250,000. One year later it was gone, much of the money having financed Diamond’s hard-partying lifestyle. It ended up at Vegas casinos, the local Lamborghini dealer — Diamond’s was jet black — and more than a few bars.

Today Diamond is in jail in Florida. His business, Diamond Ventures, was a Ponzi scheme. Authorities say he lost $15 million in bad trades, spent $15 million to keep the scheme going and pocketed at least $7 million. He was convicted of money laundering and wire fraud and sentenced to 15 years. But this story is not about Diamond. He’s just your run-of-the-mill thief.

The bigger question is, why would a smart, seasoned investor like McKenney hand over $250,000 to a guy like Diamond?

“I drank the Kool-Aid,” McKenney said. “This was my ticket to the dance. This was how the rich got richer. Everyone else was doing it.”

Everyone was doing it. It’s a sad and all-too-common rejoinder from those who fall prey to a swindle.

People hear “investment fraud” and they think of high-flying Wall Street types such as Bernie Madoff, a financier with a penthouse and private jets and, at one time, the chairmanship of the Nasdaq stock exchange. He managed billions of dollars for individuals and foundations — and built a $50 billion Ponzi scheme.

Most scams are not carried out as big institutional frauds. Rather, it is a friend or a fellow Rotarian, your accountant or even the local church deacon putting together that Ponzi scheme. He’s in your group. You have the same interests. It’s almost unimaginable that he would rip you off. It’s called “affinity fraud.” Madoff is, perhaps, the most notorious offender in this most common form of investment fraud. It’s common for good reason. It works.

Getting the guard to drop

Ruth and Len Mitchell are spending their retirement years in Arizona, light about $125,000. That’s how much they lost to longtime friend and accountant Barry Korcan. The smooth-talking Korcan joined Ruth’s skating club when she and her husband lived in Beaver, Pa., a bedroom community outside Pittsburgh. Korcan became friendly with the couple and put their money in what they thought were safe real estate investments. He set up a company called Guardian Investment Partners and provided phony quarterly statements. They thought they were earning as much as 8 percent.

Instead, Korcan enriched himself. In all, he stole $7 million from 39 investors, according to authorities. He was convicted of mail fraud and income tax evasion and is serving a seven-year prison sentence.

“He was like a son to my husband,” Ruth Mitchell said, “and he always kept a Bible on his desk.”

The pitches are almost always the same: “Get it now before it’s gone,” for impossibly high, guaranteed returns. The hustlers feed off greed and a quick-buck mentality. And they are not after the little old lady and her meager pension. The most likely victim of investment fraud is a 55-year-old, white-collar, college-educated man with a fair amount of disposable income, according to a study by the FINRA Investor Education Foundation. Just like Willie Sutton, the cons go where the money is.

“If you think you are too smart, then your guard drops and you become an easier target for the con criminal,” said Robert Cialdini, a fraud expert and psychology professor at Arizona State University.

The lure of easy money creates lemmings.

Michael Shinefield is serving an 11-year prison sentence for investment fraud. Before his sentencing, Shinefield sat down to talk. His attorneys hoped his cooperation in telling the world how cons work people over would result in a reduced sentence.

Shinefield had ripped off lots of smart Los Angeles professionals in a sports ticketing scam. He claimed to buy the tickets at face value, sell them at a premium and split the proceeds with investors. But he was no sharp, slick-talking operator.

Shinefield greeted simple questions with long pauses. Compound sentences were rare. “Ya know” and “uh” dominated as he spewed non sequiturs.

How could a guy like this attract investors?

Often he didn’t even meet the investors, he said. They heard of him through word of mouth. Shinefield paid off a few initial investors well, and they in effect became unwitting accomplices, his personal marketing team. These investors, like McKenney, drank the Kool-Aid. They listened to their friends, wanted the quick dollar and never checked Shinefield out.

If they had, they would have known that he had been jailed once for securities fraud and was not licensed to sell investments. The lesson here: Don’t take tips from friends and relatives without vetting the pitchman yourself. If he has no license or tells you the investment does not have to be registered, then watch your wallet — you are about to get scammed.

Thievery in God’s name

Perhaps the most pernicious form of affinity fraud happens at the church, synagogue or mosque. Con men love people of faith — these days, among some Christian groups, not only is it okay to be rich, it is in fact considered God’s will.

“Prosperity theology” has taken root among some Pentecostals and evangelicals who interpret the Bible as saying that Jesus wants you to prosper (get rich) while on Earth. This article of faith is often used by con criminals to scam true believers.

Belief in prosperity theology provides fertile ground for the crook prowling the pews. Although many Christians might find it disingenuous or even sleazy to be pitched an investment in church, adherents of prosperity theology consider it not only appropriate but consistent with God’s teachings.

“I’ve seen more money stolen in the name of God than any other way,” said Joe Borg, the director of the Alabama Securities Commission.

Borg has led many high-profile investigations of faith-based securities fraud, including the notorious Greater Ministries scandal. Greater Ministries was a massive con job masquerading as an evangelical church. Borg busted the group, whose leaders are now in jail. “Preachers” promised church members a 17 percent annual return on their investments, guaranteed by God. In fact, they stole almost $500 million from about 18,000 investors, mostly evangelical Christians. The deal was pitched as God’s Social Security plan.

This is certainly not confined to evangelical churches. Madoff subtlety but effectively played the religion card and enticed wealthy Jews into his scheme. The Mormon church does not want to acknowledge a problem, but there has been a rash of investment fraud in Utah and Colorado among bishops and elders of the church who have used their positions to swindle the Mormon faithful.

Jim and Diane Smart of Salt Lake City, Mormons and parents of eight, are losing their house and moving in with one of their children. They took out a $250,000 equity loan on their home to invest with a fellow church member. The church member promised returns of 20 to 25 percent in real estate investments. Instead, the Smarts say, they were scammed out of more than $200,000. The man running the scheme has been charged with fraud.

“He was in our church. We trusted him,” said Diane Smart, who has taken a job in a school cafeteria to make ends meet.

That thinking exasperates Michael Hines. The director of enforcement for the Utah state securities division, he has investigated many Mormon-related scams.

“If you need a new transmission, you go to a mechanic, not a church member. If you need brain surgery, you see a surgeon,” he said. “I don’t get why so many [Mormons] send their life savings to a church member.”

Beware of the free lunch

It was about the time I received my first AARP card that my first “free lunch” investment seminar invitation came in the mail. Lots more came after that, usually at mildly upscale places with banquet areas and mounds of fettuccine — think Tragara in Bethesda or Maggiano’s in Chevy Chase. Most free-lunch seminars are perfectly legitimate. But some are not. Either way, the folks are not giving you a free lunch because they like you.

“These free lunches and dinners, they are not gifts,” said Gerri Walsh of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, or FINRA. “They’re sales tactics designed to get your money.”

The fact that you are getting something for free plays on your age-old guilt.

“From our earliest years, we are taught that if you get something you have to give something back,” Arizona State’s Cialdini said. “The people putting on these free-lunch seminars know this. They want you to feel guilty. They want you to feel like you have to give something back in return.”

The bottom line is, if you have the time and you are hungry, go for the free lunch. But don’t turn over your pension or the equity in your home for a $11.95 plate of ziti.

Con criminals use common sales tactics, which is why so many of us fall for them: Scarcity — ad headlines scream in bold “ONLY THREE LEFT” or “THIS PRICE EXPIRES FRIDAY.” When a car salesman tells you the sale is only for “two more days,” you know, or should know, that he’s full of it. Apply that same skepticism to a broker trying to get your retirement money.

Fraudsters want to put you “under the ether.” The idea is to get you so excited and worked up about an investment opportunity that you don’t bother checking it out.

“You want to believe,” said McKenney, the Florida fraud victim. “You suspend disbelief.”

Words like that drive John Gannon nuts. He is the president of the FINRA Investor Education Foundation and a passionate advocate for honest investing.

“So many [scams] can be prevented,” he said. “It just takes a little time on your computer.”

Gannon’s team at FINRA has a Web site with a “broker check.” Type in a broker’s name and it will show lists of any infractions or complaints — and, most important, whether the broker is licensed to sell securities. The North American Securities Administrators Association offers quick links to state regulators at www.nasaa.org and has a useful tips on spotting fraud. AARP is another source.

What else can you to do protect yourself? Stop the madness. Victims routinely said they continued to invest with the con even after they had suspicions the deal might be dirty. They just didn’t want to give up hope. Good money after bad never works.

Stay away from investments you do not understand. Cons like obscure, hard-to-track products. Generally, stay clear of oil and gas deals; lots of those will be popping up, because oil is around $100 a barrel. Never, ever take equity out of your house to invest in securities. When home prices were rising, that was a favorite of the con criminals.

And finally, if you go to church, pray. Maybe do your investing elsewhere.

Carden, with video editor John Warnock, spent 18 months producing the PBS documentary “Tricks of the Trade: Outsmarting Investment Fraud.”

Link to Washington Post Article: Investment fraud isn't relegated to Wall Street: Beware the Ponzi schemer next door